As hurricane Ida pounds Louisiana and other areas of the southeast some background.

As we enter hurricane season, when there is a greater chance of more powerful storms developing in the Atlantic, here is a guide to how deadly storms form, how they are measured and why they happen where they do.

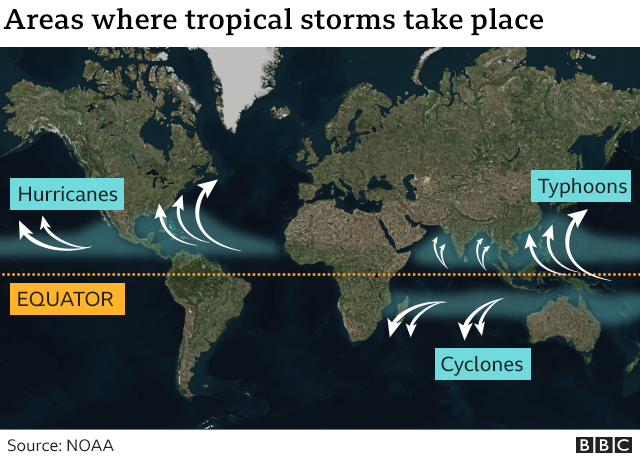

Hurricanes are the biggest and most violent storms on the planet. Every year, between June and November they hit the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico and the eastern coast of the United States, sometimes leaving a trail of destruction in their wake.

In the Pacific Ocean, they are known as cyclones. In the Indian Ocean and southern Pacific, they are known as typhoons. They are all tropical storms, but they are only called hurricanes in the north Atlantic and north-eastern Pacific.

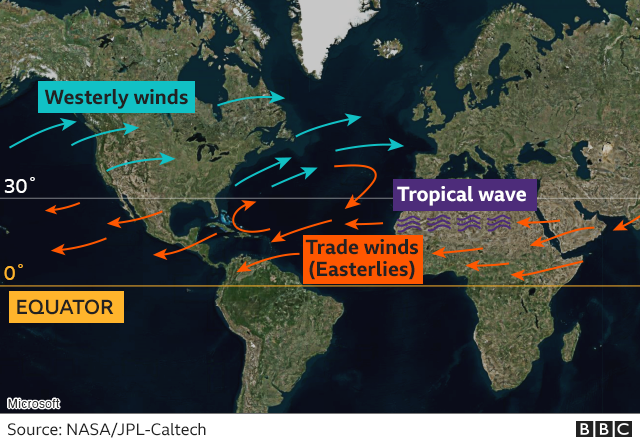

Most hurricanes that form in the Atlantic are the result of an atmospheric phenomenon known as a tropical wave.

The wave starts as a type of atmospheric trough that creates an area of relatively low air pressure – usually in western Africa, in mid-July.

If the conditions are right for it to develop, the low pressure starts to move west, with the help of the trade winds or easterlies.

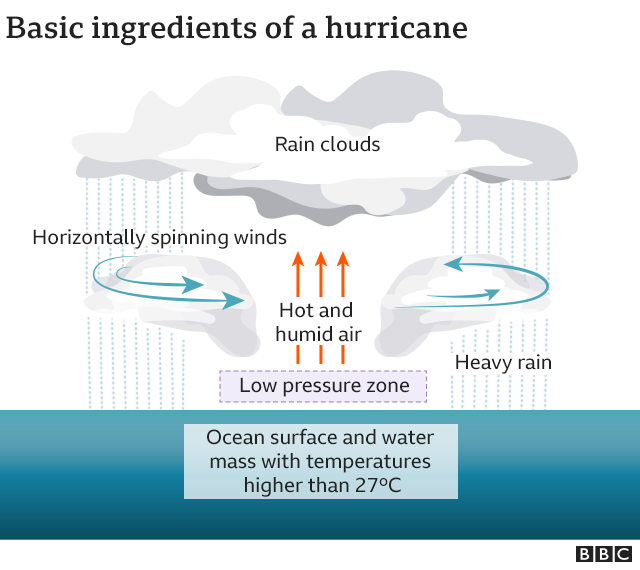

When it reaches the Atlantic, the tropical wave has the potential to become a hurricane – but for this to happen it needs enough energy in the form of heat and wind.

In fact, it needs a deep layer of warm water, with a surface water temperature above 27C.

It also needs the right winds – horizontally swirling winds to concentrate the storm and a weak vertical wind shear rising from the surface of the sea.

If the wind shear changes too much as it rises, it can disrupt the flow of heat and humidity needed to create the hurricane.

The final ingredient is a concentration of rain clouds and high humidity in the area.

This all needs to happen in the right place – generally between 10 and 30 degrees latitude in the northern hemisphere, where the rotation of the Earth helps the winds converge and rise in the area of low pressure.

When a tropical wave encounters all these elements, they all start to interact over an area between 50km (31 miles) and 100km wide.

“The movement of the tropical wave is a trigger for the storm,” says Jorge Zaval Hidalgo, general co-ordinator of Mexico’s National Weather Service.

The storm is the catalyst – and the dance of heat, air and water begins.

The area of low pressure cools the humid, warm air rising from the ocean, which fills the clouds.

The condensation of this air releases heat, which lowers the pressure even more, drawing more humidity from the ocean and the storm builds.

The winds converge and rise within the area of low pressure, spinning counter clockwise, giving the hurricane its trademark shape.

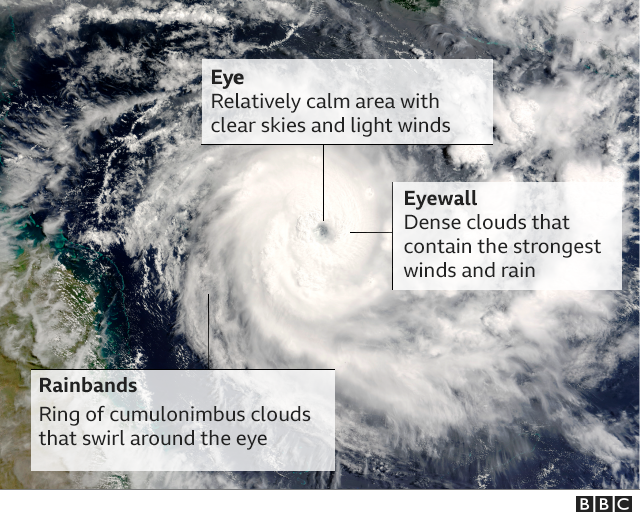

While the storm becomes more powerful, the eye of the hurricane – the central area about 30-60km wide on average – remains relatively calm.

Around it, rises the eye wall of dense clouds and most intense winds.

Beyond that are the spiral bands of cloud, where there is the most rain.

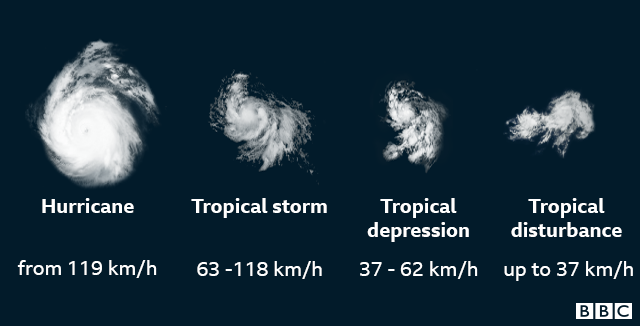

The wind speeds are what determine the moment at which we can call this phenomenon a hurricane.

At its birth, it is a tropical depression. As it gathers strength, it becomes a tropical storm. When speeds reach more than 118km an hour, it is a hurricane.

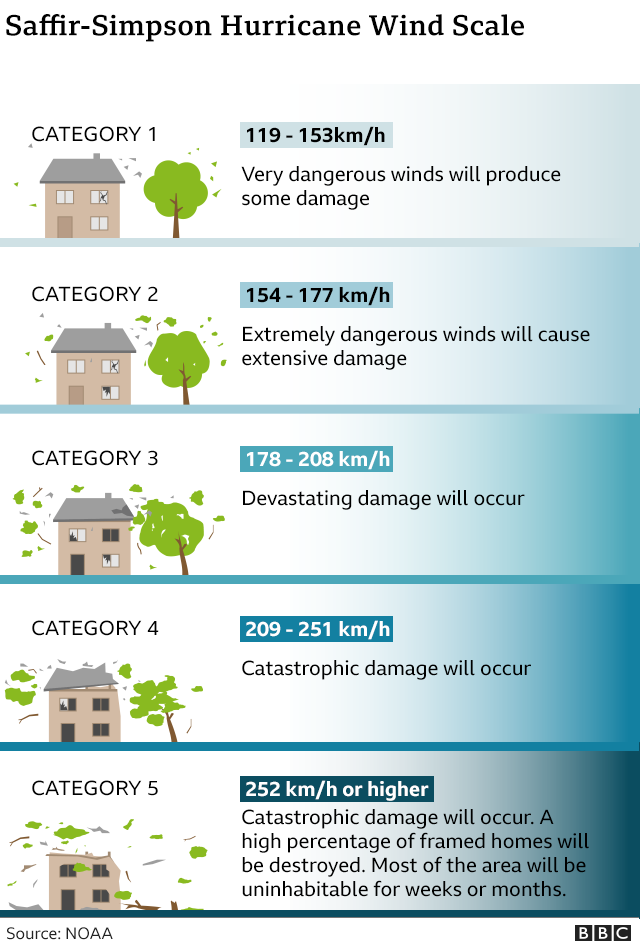

However, hurricanes can be classified in five categories depending on the sustained wind speeds. In the Atlantic, the Saffir-Simpson wind scale is used to measure their destructive power.

One hurricane’s winds can produce about half as much energy as the electrical generating capacity of the entire world, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

However, it is not the winds that cause the most destruction and loss of life, but the storm surge and flooding caused by the hurricane’s rain.

In the United States, for example, the storm surge caused by tropical cyclones in the Atlantic were responsible for nearly half of hurricane-related deaths between 1963 and 2012, according to the American Meteorological Society.

The level of destruction caused by a hurricane is also going to depend on other circumstances, such as the speed at which it hits, the terrain and local infrastructure in the affected area.

“The damage or danger associated with a tropical cyclone does not necessarily correspond to its category. For example, the highest level storm will not necessarily mean more rain,” Mr Hidalgo told the BBC.

Caught a rainbow over Winnipeg yesterday.

It was a scorching hot humid day in southern Manitoba yesterday.

Lenticular clouds (Altocumulus lenticularis in Latin) are stationary clouds that form in the troposphere, typically in perpendicular alignment to the wind direction. They are often comparable in appearance to a lens or saucer.

An arctic front has descended down the middle of North America. Even Dallas, Texas is experiencing bone chilling temps. -15 celsius in Dallas today. Winnipeg is far colder, -35 at night, -28 during the day.

If anybody is smiling it’s the natural gas providers. Lots of business. Some Winnipeg photos below.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESIce skating fever is gripping the Netherlands after days of sub-zero temperatures froze lakes, ponds and canals across the country.

Many welcomed the opportunity to don their skates amid coronavirus restrictions.

“This is the perfect reason to go out and have a little fun with the museums and everything being closed,” one woman told Reuters news agency as she strapped on her skates in Amsterdam on Friday.

But officials have urged people to stay close to home and avoid crowds to prevent the spread of Covid-19.

Dozens of skaters briefly glided along the surface of Amsterdam’s historic Prinsengracht canal on Saturday.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTEPA

IMAGE COPYRIGHTEPAIt was the first time since 2018 that skating there had been possible, reports said.

“It’s a once-every-so-many-years experience, so when you get the chance, do it,” one man told the Associated Press news agency.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTEPA

IMAGE COPYRIGHTEPAElsewhere in the country, people made the most of frozen lakes, ponds and canals before a thaw expected to begin in coming days.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTNURPHOTO VIA GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTNURPHOTO VIA GETTY IMAGES IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES IMAGE COPYRIGHTREUTERS

IMAGE COPYRIGHTREUTERSAt the frozen Nannewiid lake in the north of the country, groups played hockey, parents pulled their children along on sledges, and dogs took to the ice.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESOur correspondent Anna Holligan shared photos of people enjoying the ice in The Hague.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTANNA HOLLIGAN/BBC

IMAGE COPYRIGHTANNA HOLLIGAN/BBC IMAGE COPYRIGHTANNA HOLLIGAN/BBC

IMAGE COPYRIGHTANNA HOLLIGAN/BBC“Take advantage of the good weather and the ice, but do it under Covid-19 measures,” Prime Minister Mark Rutte told a news conference on Monday. “You can skate with another person, but what you can’t do is organise big competitions. Unfortunately that doesn’t work.”

BBC

On Thursday Las Vegas had an unusual snowfall. Las Vegas does see snow flurries every couple years but the snow usually melts as soon as it hits the ground. The snow on Thursday was different as in some areas of the Las Vegas valley the snow stayed on the ground for a few hours before it melted away.