Human beings never cease to amaze. What possessed these people to start carving stones into spheres. It must have taken months or years to complete one of these. Some people just have too much time on their hands. But then maybe it wasn’t humans who did this, does the term Space Aliens come to mind?

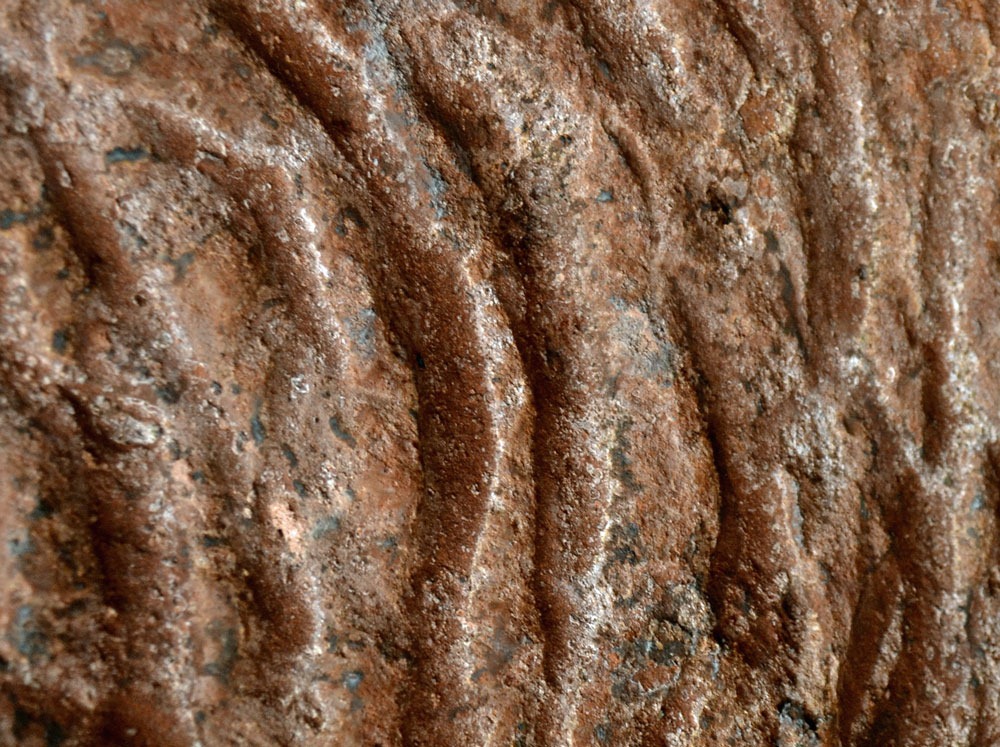

The stone spheres (or stone balls) of Costa Rica are an assortment of over three hundred petrospheres in Costa Rica, located on the Diquis Delta and on Isla del Caño. Known locally as Las Bolas, they are also called The Diquis Spheres.

The spheres range in size from a few centimetres to over 2 metres (6.6 ft) in diameter, and weigh up to 16 short tons (15 t). Most are sculpted from gabbro, the coarse-grained equivalent of basalt. There are a dozen or so made from shell-rich limestone, and another dozen made from a sandstone.

The stones are believed to have been carved between 200 BC and 1500 AD. However the only method available for dating the carved stones is stratigraphy, and most stones are no longer in their original locations. The culture of the people who made them disappeared after the Spanish conquest.

Spheres have been found with pottery from the Aguas Buenas culture (dating 200 BC – AD 600) and also they have been discovered with Buenos Aires Polychrome type sculpture (dating 1000 – AD 1500). They have been uncovered in a number of locations, including the Isla del Caño, and over 300 kilometres (190 mi) north of the Diquis Delta in Papagayo on the Nicoya Peninsula.

The spheres were discovered in the 1930s as the United Fruit Company was clearing the jungle for banana plantations. Workmen pushed them aside with bulldozers and heavy equipment, damaging some spheres. Additionally, inspired by stories of hidden gold workmen began to drill holes into the spheres and blow them open with sticks of dynamite. Several of the spheres were destroyed before authorities intervened. Some of the dynamited spheres have been reassembled and are currently on display at the National Museum of Costa Rica in San José.

The first scientific investigation of the spheres was undertaken shortly after their discovery by Doris Stone, a daughter of a United Fruit Co. executive. These were published in 1943 in American Antiquity, attracting the attention of Samuel Kirkland Lothrop of the Peabody Museum at Harvard University. In 1948, he and his wife attempted to excavate an unrelated archaeological site in the northern region of Costa Rica. The government of the time had disbanded its professional army, and the resulting civil unrest threatened the security of Lothrop’s team. In San José he met Doris Stone, who directed the group toward the Diquís Delta region in the southwest (“Valle de Diquís” refers to the valley of the lower Río Grande de Térraba, including the Osa Canton towns of Puerto Cortés, Palmar Norte, and Sierpe) and provided them with valuable dig sites and personal contacts. Lothrop’s findings were published in Archaeology of the Diquís Delta, Costa Rica 1963.