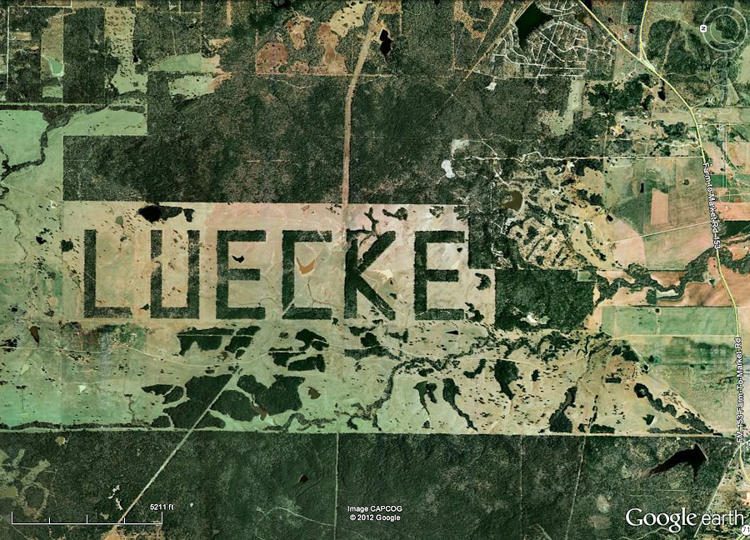

The Soviet lunar program was covered up, forgotten after failing to put a man on the moon.

Soviet scientists were well ahead of their American counterparts in moon exploration before President John F. Kennedy pronounced the U.S. would put a man there first. The Soviets had already landed the probe Luna 2 on the surface of the moon in 1959 and had an orbiting satellite in 1966.

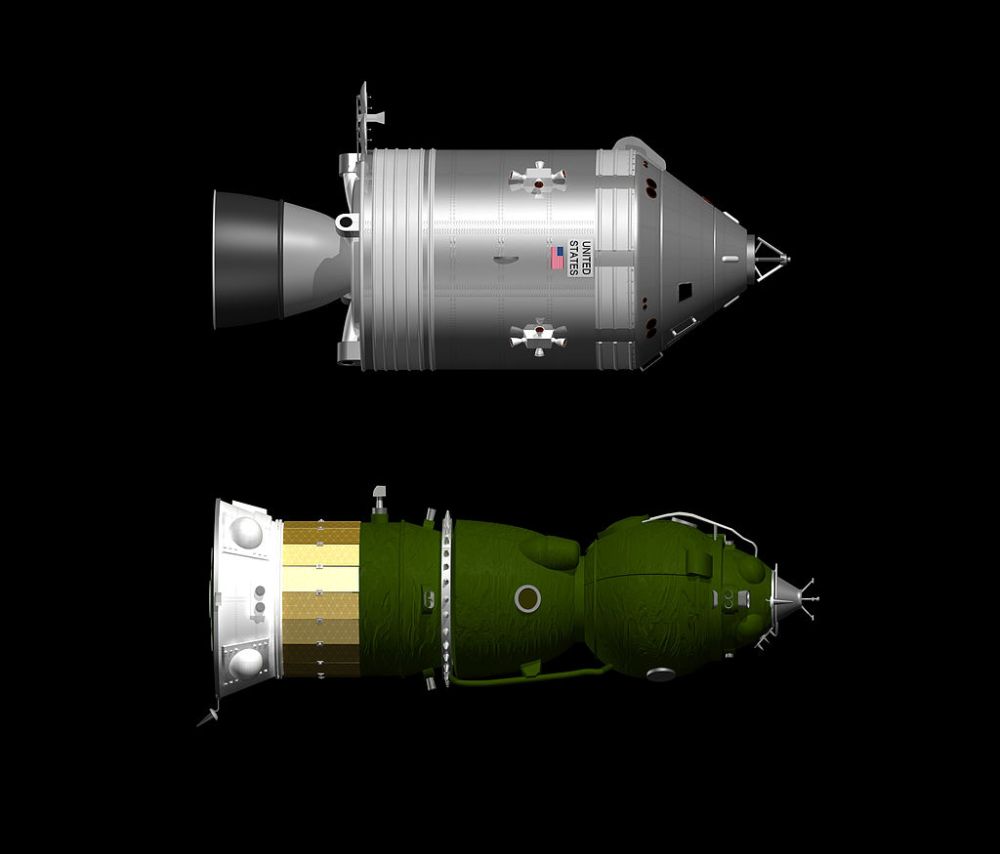

The Soviets developed a similar multi-step approach to NASA, involving a module used to orbit the moon and one for landing. Their version was decidedly less complex and lighter to account for inferior rockets. This photo show the LK “Lunar Craft” lander, which has a similar pod-over-landing gear structure but numerous key differences.

All the activities done by two astronauts is done by one. To make the craft lighter, the LK only fits the one cosmonaut, who was supposed to peer through a tiny window on the side of the craft to land it. After landing the vehicle the pod separates from the landing gear, as with the Apollo Lunar Module, but uses the same engine for landing as it does for take off as another weight savings.

The L2 Lunar Orbit Module designed to transport the LK into orbit around the moon was similarly stripped down. There’s no internal connection between the two craft so the cosmonaut had to space walk outside to get into the LK and head towards the surface. When the LK rejoined the L2 for the return trip home, the now likely exhausted cosmonaut would then climb back out into the abyss of space. The LK would then be thrown away.

Soviet Lunar Orbiter

Soviet Lunar Lander (LK)

There were numerous political, scientific and financial reasons why the Soviets didn’t make it to the moon first, including a space agency with split priorities and therefore not single-mindedly dedicated to this goal. Neil Armstrong walked on the moon first on July 20, 1969, besting the Russians, who were still planning to visit the moon in the upcoming years.

They had the equipment, but they didn’t have the rockets.

Getting to the moon requires launching a command module and a lander. Both are heavy objects and require massive amounts of thrust to get into orbit. The Soviet’s planned to use their N-1 rocket, but two failed launches in 1971 and 1972 destroyed dummy landing and control modules, as well as the rockets themselves, and led to the program being shelved for lack of a proper launch vehicle.

The LK was sent into space for numerous test missions. The first two unmanned flights were successful tests of the vehicle through a simulated orbit. The third flight ended when the N-1 rocket crashed. The fourth test in 1971 was a success, but years later the decaying test module started to return to Earth with a trajectory that would put it over the skies of Australia.

NASA explains in a report on the Soviet space program how they had to convince the Australians it wasn’t a nuclear satellite:

To allay fears of a nuclear catastrophe, representatives of the Soviet Foreign Ministry in Australia admitted that Cosmos 434 was an “experiment unit of a lunar cabin,” or lunar lander

Eventually, the program was deemed too expensive and unnecessary in light of the NASA success. The Soviets moved onto building space labs, successfully, and the remaining parts of the lunar program were destroyed or dispersed, including this amazing collection of parts hidden in the back of the Moscow Aviation Institute.

American Lunar Orbiter top, Soviet Orbiter bottom

Soviet Lander ascending from the surface of the Moon, artist graphic.

‘LK Lander and Apollo LM (drawn to scale). Manned Moon landers