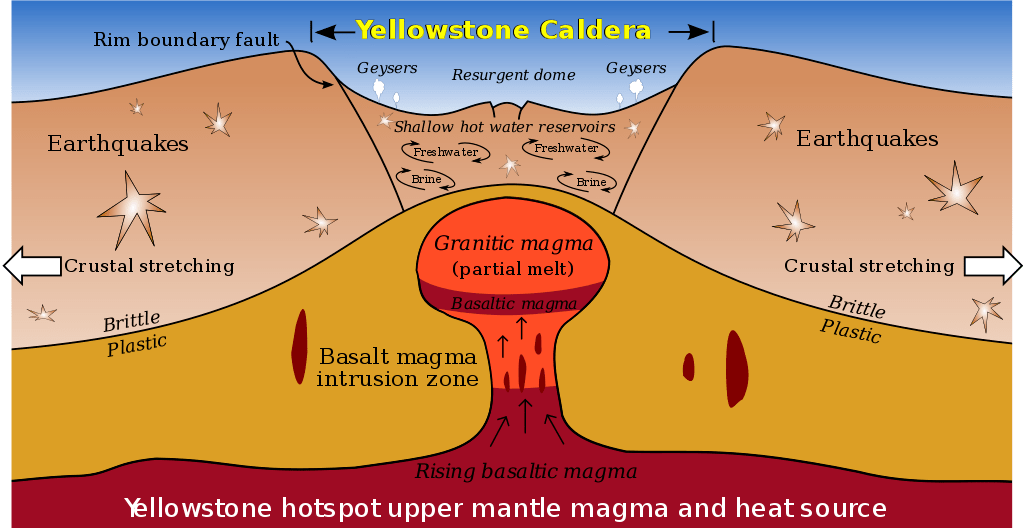

The supervolcano that lies beneath Yellowstone National Park in the US is far larger than was previously thought, scientists report.

A study shows that the magma chamber is about 2.5 times bigger than earlier estimates suggested.

A team found the cavern stretches for more than 90km (55 miles) and contains 200-600 cubic km of molten rock.

The findings are being presented at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting in San Francisco.

Prof Bob Smith, from the University of Utah, said: “We’ve been working there for a long time, and we’ve always thought it would thought it would be bigger… but this finding is astounding.”

If the Yellowstone supervolcano were to blow today, the consequences would be catastrophic.

The last major eruption, which occurred 640,000 years ago, sent ash across the whole of North America, affecting the planet’s climate.

Now researchers believe they have a better idea of what lies beneath the ground.

The team used a network of seismometers that were situated around the park to map the magma chamber.

Dr Jamie Farrell, from the University of Utah, explained: “We record earthquakes in and around Yellowstone, and we measure the seismic waves as they travel through the ground.

“The waves travel slower through hot and partially molten material… with this, we can measure what’s beneath.”

The team found that the magma chamber was colossal. Reaching depths of between 2km and 15km (1 to 9 miles), the cavern was about 90km (55 miles) long and 30km (20 miles) wide.It pushed further into the north east of the park than other studies had previously shown, holding a mixture of solid and molten rock.

“To our knowledge there has been nothing mapped of that size before,” added Dr Farrell.

The researchers are using the findings to better assess the threat that the volatile giant poses.

“Yes, it is a much larger system… but I don’t think it makes the Yellowstone hazard greater,” explained Prof Bob Smith.

“But what it does tell us is more about the area to the north east of the caldera.”

He added that researchers were unsure when the supervolcano would blow again.

Some believe a massive eruption is overdue, estimating that Yellowstone’s volcano goes off every 700,000 years or so.

Although fascinating, the new findings do not imply increased geologic hazards at Yellowstone, and certainly do not increase the chances of a ‘supereruption’ in the near future. Contrary to some media reports, Yellowstone is not ‘overdue’ for a supereruption.

Media reports were more hyperbolic in their coverage.

A study published in GSA Today, the monthly news and science magazine of the Geological Society of America, identified three fault zones where future eruptions are most likely to be centered. Two of those areas are associated with lava flows aged 174,000–70,000 years, and the third is a focus of present-day seismicity.

In 2017, NASA conducted a study to determine the feasibility of preventing the volcano from erupting. The results suggested that cooling the magma chamber by 35 percent would be enough to forestall such an incident. NASA proposed introducing water at high pressure 10 kilometers underground. The circulating water would release heat at the surface, possibly in a way that could be used as a geothermal power source. If enacted, the plan would cost about $3.46 billion. On the other hand, according to Brian Wilson of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, such a project might trigger rather than prevent an eruption.

![namib-desert-meets-sea-4[2]](https://markozen.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/namib-desert-meets-sea-42.jpg?w=700)

![namib-desert-meets-sea-2[2]](https://markozen.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/namib-desert-meets-sea-22.jpg?w=700)

![namib-desert-meets-sea-7[2]](https://markozen.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/namib-desert-meets-sea-72.jpg?w=700)